The United States, the Middle East and world oil markets are bracing for Iran’s response after President Donald Trump launched punishing strikes on Iranian nuclear energy sites overnight, plunging the region into an unprecedented new phase of a decades-old conflict.

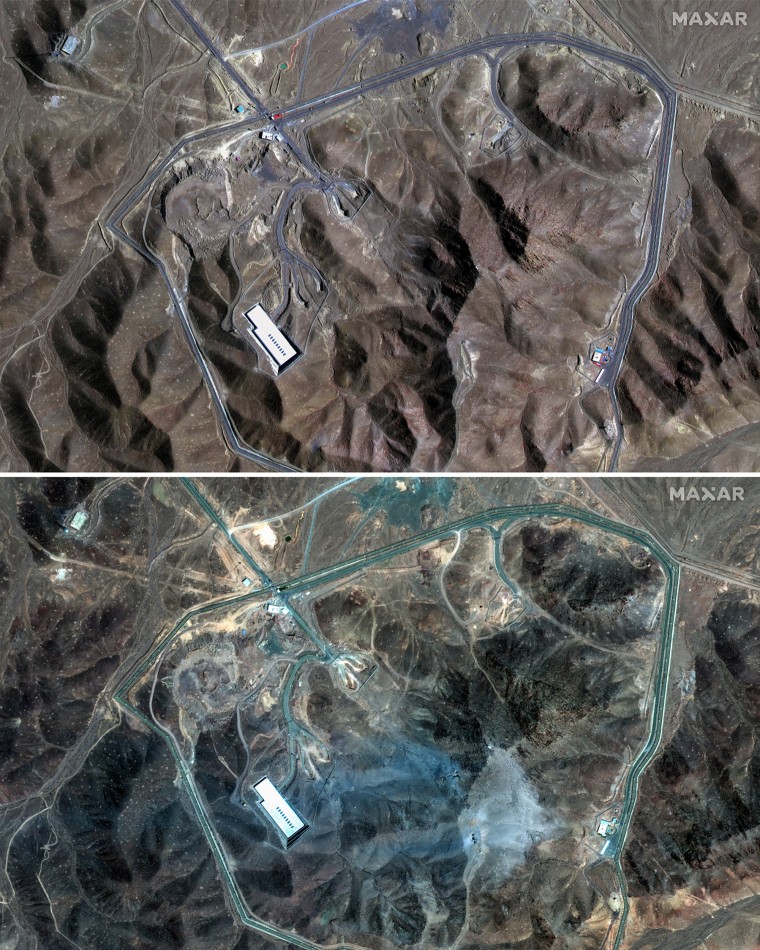

The U.S. struck Iranian nuclear facilities, including the key Fordo site, with 14 GBU-57s, 30,000-pound “bunker buster bombs,” according to the U.S. military. It was the first time the United States has directly bombed the Islamic Republic.

Follow along for live coverage.

The next 48 hours are of particular concern, according to two defense officials and a senior White House official. It’s unclear whether any retaliation would target overseas or domestic locations, or both, the officials said.

In the days before Trump gave the final order for the attack on the nuclear sites, Iran sent a private message to the president that it would respond to such a move by unleashing terrorist attacks on U.S. soil carried out by sleeper cells operating inside the country, according to two U.S. officials and a person with knowledge of the threat.

The warning was conveyed to Trump by an intermediary during the G7 summit in Canada, the three sources said. Trump left the G7 early on June 16, saying he needed to return to Washington to monitor the intensifying conflict between Iran and Israel.

The White House did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The Iranian Mission to the United Nations declined to comment.

U.S. bases and assets have been at their highest state of alert for months, but after Israel began warring with Iran on June 13, the officials, who spoke earlier in the week, said concerns were heightened even more about the potential for attacks on U.S. assets from Iran or its proxies in the region.

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi, meanwhile, warned of “everlasting consequences.”

Iran has long relied on asymmetric tactics against stronger foes, including terrorist attacks. In 1983, the U.S. accused Iran of orchestrating the bombings of a Marine barracks and embassy in Beirut through its Lebanese proxy, Hezbollah, killing hundreds.

But it is not clear that Iran could carry out a terrorist attacks inside the United States. In the past, Tehran has struggled to carry out operations on American soil, using hired hitmen that have botched their missions, according to U.S. authorities.

With fewer reliable partners in the Middle East and little regional appetite for a wider war, experts say that Tehran faces a narrower set of options and a sharper set of risks as it weighs how to respond.

“They’re really stuck,” H.A. Hellyer, a senior associate at the London-based Royal United Services Institute, told NBC News. “If they fight back by striking American targets, then the U.S. is very likely to respond with a much more aggressive and continual campaign that could cause even more damage, not only to the regime, but to the country at large.”

“But if Iran doesn’t respond, the cohesion of its regime,” a ruling class weighed down by corruption, public discontent and growing disillusionment with its promises of resistance, “could really be challenged,” he added.

As they weigh their response, Iranian leaders will have one eye on their restive population, experts said. An open-ended conflict with Israel and the United States could pose a threat to the regime itself, said Jonathan Panikoff, a former career intelligence officer now at the Atlantic Council think tank.

Recognizing it is no match for U.S. and Israeli military power, Iran may choose a more limited response that would leave it a way out of the confrontation, he predicted.

After the U.S. killed top Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in a January 2020 drone strike ordered by Trump in his first term, Iran launched a barrage of missiles at U.S. bases in Iraq that wounded dozens but caused no fatalities. Some U.S. officials and regional analysts at the time viewed the Iranian response as calibrated, a way to send a message without igniting a full-blown war with America.

Given the apparent weakness of Iran’s air defenses, which Israeli jets have targeted for the last two weeks, Iranian leaders may choose the option of waiting until they can regroup and organize retaliatory action. In some cases in the past, Iran has targeted Iranian critics abroad years after they left the country.

“In the end, they are going to try to be calculated and narrow about how they respond,” Panikoff said.

Potential missile attacks

Since Israel’s initial attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, Iranian missiles have pierced the country’s vaunted missile-defense system, the Iron Dome, reduced apartment blocks to rubble, and killed at least 24 people. After the U.S. attacks, the nation launched a missile barrage into Israel on Sunday morning, causing damage and injuries in Tel Aviv.

“Iran will try to redouble its efforts against Israel in order to show its determination to inflict damage on its arch enemy,” said Fawaz Gerges, a professor of international relations at the London School of Economics. “We are likely to witness major escalation between Iran and Israel in the next few days.”

However, Gerges added, Iran will try and avoid “being dragged into an all-out war with the United States.”

In the Persian Gulf, Arab states that host key U.S. air and naval bases “are terrified right now” about possible Iranian retaliatory missile or drone strikes on American targets in their territories, according to Panikoff.

Iran’s Revolutionary Guard argues that the sheer number and spread of U.S. bases in the region, where it has some 40,000 troops, are not a strength, but a “point of vulnerability.”

The U.S. has bases in Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, among other countries. Last week, it moved some aircraft and ships that may be vulnerable to a potential attack, and has limited access to its al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

But it’s unclear whether Iranian missiles could reach U.S. or allied forces in the Gulf without being shot down. Israel has managed to intercept many of the ballistic missiles and drones that Iran has launched over the past week.

Hellyer, the senior associate at the Royal United Services Institute, said Iran still has the power to launch missile attacks, “but only because Israelis haven’t taken out all of their missile launchers.”

Iran still has around 40% of its launchers, Hellyer said, “so the threat hasn’t been removed in that regard, but they’ve been degraded quite a lot.”

On Sunday, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said that while the U.S. did not want war, it will “act swiftly and decisively when our people, our partners or our interests are threatened.”

Blocking oil flows

In what could prove to be a symbolic move, Iran’s parliament voted Sunday to block the Strait of Hormuz between Iran and Oman, a strategic waterway through which a fifth of global oil passes. The final decision will be made by the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The strait is an international shipping choke point and blocking it could send oil prices soaring. It would also hurt Iran’s own struggling economy and alienate neutral powers.

China, which is Iran’s top customer for its oil exports, would likely strongly object to any Iranian attempt to disrupt oil shipping lanes, experts said.

In the 1980s, Iran paid a heavy price when it targeted commercial vessels and U.S. Navy ships in the Persian Gulf during the Iran-Iraq War. In 1988, after a U.S. ship struck a sea mine planted by Iran, American naval forces sunk three Iranian warships and disabled two Iranian oil platforms.

Since that lopsided military clash, Iran has not tried to blockade the Strait of Hormuz.

Weakened proxies

Iran’s proxy network has also been battered by years of attrition with Israel and the U.S.

Its most important ally, Hezbollah in Lebanon, has been devastated by a series of Israeli attacks and assassinations, and had indicated it would not join the fight against Israel.

The Houthis, Hezbollah and Iraqi Shiite militias are unlikely to have much impact on Israel and the United States’ struggle with Iran. In the Palestinian enclave of Gaza, Hamas — which Iran armed and trained — has been badly weakened and its leaders have been killed.

Iran may also lack staunch support from its neighbors. Some Gulf nations, including Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, stopped short of condemning the U.S. attacks on Iran, calling instead for de-escalation.

“The rest of the region is very opposed to this war and doesn’t want it and didn’t want it, but they’re also not able to affect the outcome,” Hellyer said.

As a result, an increasingly isolated Iran has “no friends to speak of,” he said.

Cyber threats

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ cyber capabilities are formidable, and the U.S. considers Iran one of its four major adversaries in cyberspace along with China, North Korea and Russia.

While Iran lacks Russia’s robust cybercrime syndicates or China’s vast teams of sophisticated digital spies, the U.S. has in recent years accused Iranians of working for the IRGC. These allegations have included the hacking of American defense companies and federal agencies as well as conducting ransomware attacks on critical American infrastructure.

At times, Iran has responded to American attacks with thematically linked cyberattacks. After the U.S. and Israel deployed the Stuxnet virus in 2009 to degrade Iranian centrifuges, the IRGC attempted to remotely hack several power facilities, including the Bowman Dam in New York. After Las Vegas Sands Casino owner Sheldon Adelson called for the U.S. to bomb Tehran, Iranian hackers allegedly broke into company computers and deleted everything they could, costing the Sands an estimated more than $40 million.

If Iran conducts retaliatory cyberattacks, they would come in the wake of several rounds of cuts by the Trump administration to its top civilian cyber defense agency, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. CISA’s two former directors have both warned that the administration’s cuts make U.S. infrastructure more vulnerable to hackers.